In the words of Brad Feld, “(e)ntrepreneurs can’t build great companies alone…Startups require talent and expertise of a technical, business, managerial and temperamental nature.” This is particularly true in the Balkan region where entrepreneurship is a relatively new phenomenon, developing in a context of rapid social, cultural and economic change. While entrepreneurs may survive and even thrive on the local market working alone or in a very small team, the global market requires an entirely different setup. If the entrepreneur’s ambition is growth and international expansion the availability of local talent becomes a requirement, and often a challenge.

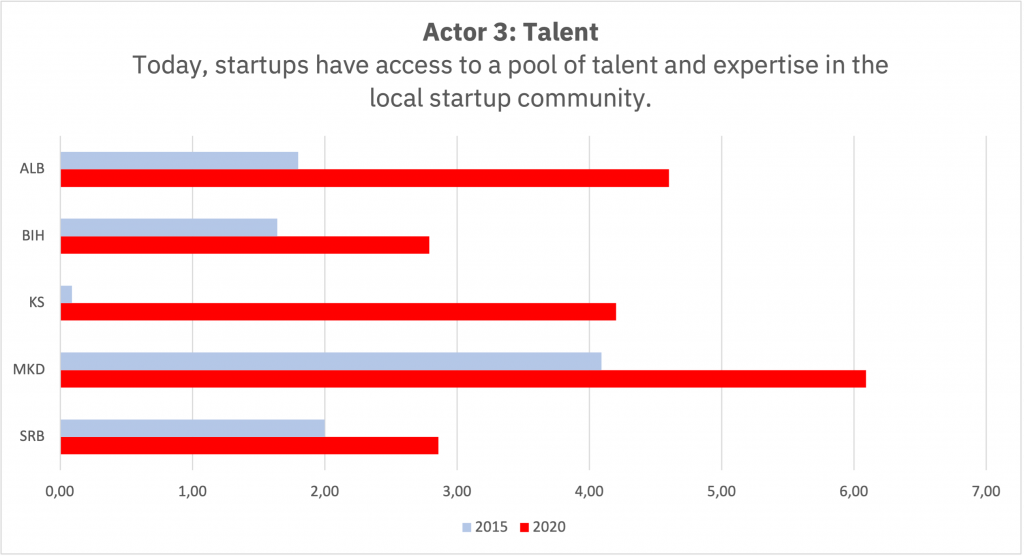

On the topic of talent, we asked our interviewees how accurate they found the following statement “Today, startups have access to a pool of talent and expertise in the local startup community.“

Again, the interviewees did not find the statement accurate. Clearly, access to talent and expertise is a key challenge to startups in the region. However, the situation appears to be improving, albeit from a very low level. In 2015, the score was 2.5 (on a scale from 0 to 10), meaning there was almost complete disagreement with the statement. Five years later, the score is 4.1, which still represents an improvement of 64%. The change is positive in all five countries – Albania (+156%) and Bosnia & Herzegovina (+75%), followed by North Macedonia (+49%), Serbia (+45%) and Kosovo (+40%).

Despite this positive trend, it becomes clear from every conversation with startups founders in the region that access to people with talent and expertise is a crucial obstacle, if not the number one challenge, with which growth-oriented startups struggle daily. The fact that the countries appear incapable of producing a workforce qualified and large enough to satisfy the human resource needs of one of the few dynamic sectors of their respective economies is odd, to say the least, in particular when taking into consideration the very high youth unemployment data in these countries. Bridging this gap between supply and demand for IT talent for the benefit of the local private sector should be a no-brainer for governments set on reducing unemployment.

Yet, there appears to be a well-documented mismatch between the formal education system (supply) and companies in the tech sector (demand), which has been going on since the beginning of the transition process 30 years ago. The obvious solution would be for governments to introduce entrepreneurship as a subject in primary and secondary schools, while universities invest more in entrepreneurial practices. But, reality says that this is a long shot. In the short-term, the private sector is not waiting for the public sector and the formal education sector. Instead, entrepreneurs themselves are filling the human resource gap to the best of their abilities. Some are starting their academies to fulfill their talent needs, while others, such as SEDC and Brainster in North Macedonia, create talent and expertise building solutions in the non-formal education sector.

Private solutions to the access to talent challenge are a positive development. Unfortunately they will never generate the required transformational change in the system. Specifically, while the private sector may build talent among thousands of persons per year, to give the entire ecosystem a talent boost in a systematic way, the governments must take action and invest in creating tens of thousands of potential entrepreneurs and startup staff on an annual basis. Such an increase in the quality and quantity of the pool of local talent and expertise will benefit and boost local startups. At the same time, it will attract international startups to the region as a new form of high-value Foreign Direct Investment (FDI).