Brad Feld’s definition of Entrepreneurial Support Organizations (ESO) is quite broad. It Includes “…startup accelerators, incubators, and studios, co-working facilities, innovation spaces, hackerspaces, maker spaces…as well as…industry, membership, entrepreneurship, networking, event, and facilitation organizations and associations”. For these ecosystem actors, startups are the key focus.

In the context of the Balkan entrepreneurial ecosystems, some actors are more present than others now. While co-working facilities can now be found in almost every larger town, few incubators and even fewer accelerators operate. Hacker- and maker-spaces are even more rare.

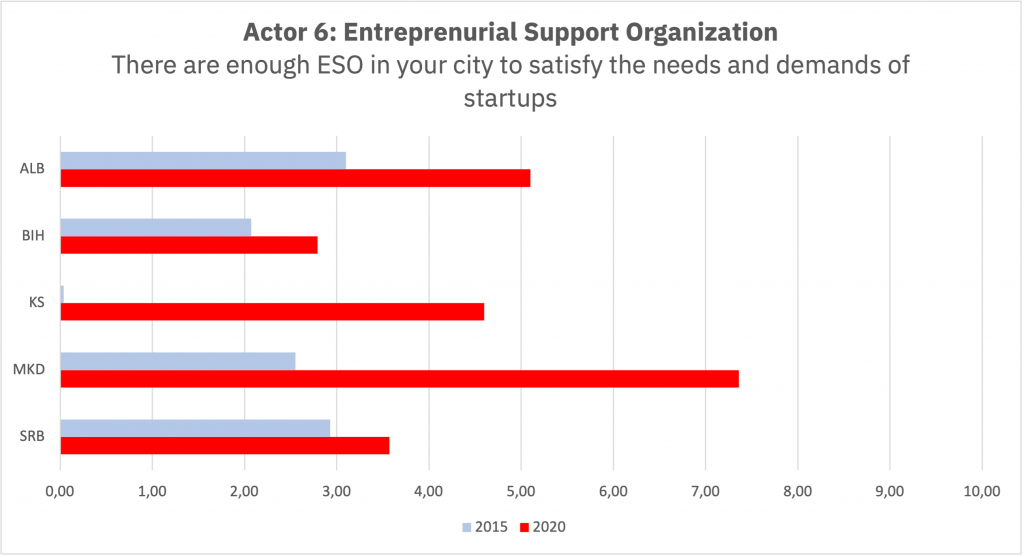

On the topic of Entrepreneurial Support Organizations, we asked our interviewees how accurate they found the following statement “There are enough ESO in your city to satisfy the needs and demands of startups”.

Here the interviewees’ answers pointed towards a positive trend, meaning that ESOs are doing a better job than five years ago in meeting the needs and demands of startups. In 2015, the average score was 2.92 (on a scale from 0 to 10), meaning there was a weak supply of ESO services available to startups. In 2020, the score was 4.7, representing an improvement of 61%. The change is positive in all five countries:

- Albania (+65%) – the jump in the right direction is most likely a reflection of the numerous new startup support programs recently launched and completed.

- Bosnia & Herzegovina (+33%) – there appears to be a stagnation in programs, with a few private initiatives as noticeable exceptions to an otherwise very donor-driven development.

- North Macedonia (+196%) – growth can partially be linked to the Fund for Innovation and Technology Development (FITD) and its support to three accelerators (Seavus, XFactor and UKIM), and partly to the establishment of Startup Macedonia and a variety of NGO driven initiatives in Skopje and selected other towns.

- Serbia (+24%) – mature and experienced ESOs, such as ICT Hub and Digital Serbia Initiative are in the process of consolidation, while new private organizations are filling in niche markets and verticals, such as gaming and blockchain.

- Kosovo (+15%) – The minimal improvement most certainly is linked to the entrance and growth of VentureUP incubator, implementing a variety of programs in quick succession targeting youth, green economy, tourism and more.

While the interviewees recognize improvement in the overall supply of services to startups by ESOs , this is only half the story. The ecosystems in the Western Balkans are relatively young, which means ESOs are not yet capable of fully addressing the needs and demands of startups as they grow. In fact, most ESOs appear to address startups in the idea stage, mainly because this is where most of the international donor agencies are active and engage NGOs to implement their programs. In some countries, such as Albania, this recently resulted in an over-supply of programs in relation to available startups.

There is a need for more and better coordination between governments, donor agencies and startup communities to ensure that startups have consistent access to quality technical assistance and adequate financial instruments at every stage of their development.

Another critical need that must be addressed to create viable ecosystems in the region capable of delivering quality support to startups is to increase the involvement of VCs, business angels and corporations as ESOs and/or as supporters of existing ESOs. Without private sector involvement and private capital utilization, the development of the Balkan ecosystems will remain dependent on public money. This dependency severely limits how far we can expect to travel.