The key actor in any entrepreneurial ecosystem is obviously the individual entrepreneur. It’s the entrepreneur who transforms an idea into a viable business model and drives the change and growth processes. However, one swallow does not make a summer. There is a need for a critical mass of entrepreneurs to inspire and drive transformational change in the economy and in society. This is particularly true in the Balkans where entrepreneurial ecosystems and entrepreneurs represent mindset change, a change in culture, where optimism, creativity, critical thinking, experimentation, problem-solving and giving back are now increasingly highlighted and rewarded.

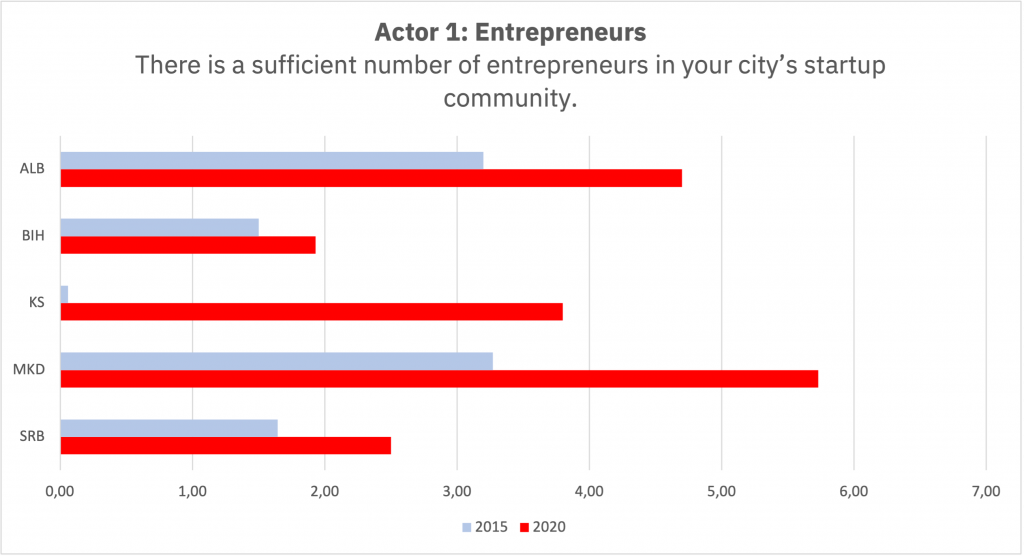

In the words of Brad Feld, it’s crucial for the success of the startup community that there is a sufficient number of entrepreneurs who can be experienced and serial, but also “novice or inexperienced entrepreneurs, and aspiring, nascent or even dormant entrepreneurs”. Therefore, we asked our interviewees how accurate they found the following statement “There is a sufficient number of entrepreneurs in your city’s startup community.“

Overall, looking at the accumulated feedback from the five countries, the answer is No! The interviewees do not think that there is a sufficient number of entrepreneurs in their respective startup communities. On average, we see a significant improvement (56%) compared to 5 years ago, but it’s happening from a very low level. On a scale from 0 to 10, the score was a mere 2.7 in 2015, which means there was an almost universal agreement among the interviewees in the five countries that the startup communities were very low on entrepreneurs back then.

That said, there are significant differences between the countries. Bosnia & Herzegovina and Serbia scored very low in 2015 at 1.5 and 1.6 respectively, but in the last 5 years Serbia grew with 56% and BIH only by 23%. It appears that the creation of a new generation of entrepreneurs is going slower in BIH, than in other countries such as Albania (+47%), Kosovo (+58%) and North Macedonia (+73%). There is a common realization among the interviewees that things would look very different in their respective startup communities if there were only more entrepreneurs.

The challenge of building a funnel capable of creating a steady flow of new entrepreneurs appears to be linked to two variables:

- startup support programs, and

- the education system.

There is a common theme among the interviewees that business creation is somehow linked to the availability of business support programs, and access to grant schemes, in particular. In most countries, programs and grant schemes are associated with projects funded by international donor agencies. At best, such programs are regularly available to local entrepreneurs, but too often, they happen on a one-off basis, making it difficult for new entrepreneurs to adjust their business development to accommodate the program schedule, rather than the other way around.

As one interviewee remarked, “there needs to be a pipeline process in place where startup support opportunities are structured and coordinated. For example, startup weekends and bootcamps take place in the Spring, and they feed entrepreneurs into acceleration programs in the Autumn.” Another interviewee highlighted the need for more entrepreneurs to be more serious as entrepreneurs, highlighting the risk of too many grant schemes attracting the wrong kind of people, people driven by access to free money rather than the desire to grow a business. The jumping of a team from one grant scheme to another feeds a negative dependency culture which is contra-productive, as we seek to encourage mindset change among the next generation of entrepreneurs.

Other interviewees pointed to the chronic failure of the formal education system to create entrepreneurs. In more mature ecosystems, much is made of the role of universities in encouraging free-thinking and problem-solving and introducing students to the realities and opportunities of the private sector. This, unfortunately, is not yet happening in any structured form in the Balkans, and often the way around this academic bottleneck appears to be a variety of entrepreneurship boosting solutions in the non-formal education space.

This all points to the need of more structured and well-funded interventions by the state, as a public policy creator, with the aim of raising awareness about entrepreneurship as a career choice among students creating the space, time and resources for students of all ages to experience the entrepreneurial spirit. As some Balkan governments declare their ambition to be more supportive of startups, to invest in the creation of the next generations of entrepreneurs, this should be a no-brainer solution.